My Sum-Up Of Big Data Concepts

This summer, I carried out an internship in a young startup in Rouen, Normandy, France: Creative Data. Part of the subject of my internship was to work on Big Data technologies so I spent quite some time learning things about Big Data. This post sums up the main concepts and my thoughts about this.

We will see:

- Why Big Data?

- To a distributed and simplified approach

- Hadoop

- Sum-up of Big Data technologies

- Hadoop distributions

- Big Data evolution: the progression of Spark and the end of MapReduce

- Hadoop in the cloud

Why Big Data?

Note that in this post, by “current technologies”, I mean non-Big Data technologies, which is of course not true.

People often say that Big Data answers at least one of the 3V problems, that is:

- Volume: The volume of data that we need to process increase dramatically, and classical solutions often don’t scale well and have problems with this volume increase. Current solutions run on one machine and adding capacity to one machine isn’t possible for technical and cost reasons.

- Variety: Data aren’t always structured (coming from relational databases (RDBMS)) but more and more semi-structured or even not-structured (texts, images, logs, etc.). Current solutions often works with structured data.

- Velocity: Time can be crucial, and classical solutions can be slow, still for scalability reasons.

Big Data solutions aim to respond to at least one, and often more of these components. I personally consider that Big Data do not bring new data processing techniques (techniques such as Business Intelligence or Data Mining), but rather new implementations of those general techniques to comply with new constrains due to Big Data.

To a distributed and simplified approach

We have seen that the problems with current solutions is that they are too strict concerning data format (Variety) and non-scalable (Volume and Velocity).

To meet the requirements we’ve seen, Big Data technologies are highly distributed to run processes on a cluster of multiple servers working together. This distrusted approach allows to “simply” meet scalability requirement and allows to cumulate modest servers and add new machines up to the point when you meet the performance that you want for your cluster.

To meet the variety requirement, Big Data approach are often “simplified” in the sense that it is much more flexible than RDBMS. For example, most Big Data solution use a schema-on-read approach that is to say you match your raw data to your schema when to read the data, whereas RDBMS often are schema-on-write so your data must match a predefined schema when you write it.

Still in the same idea of simplicity, most of Big Data solutions let the user choose in which format data is stored, either a raw format such as CSV or a serialized/compressed one like Parquet, whereas most RDBMS handle data storage in their own way.

Hadoop

A few research allows you to realize that Hadoop is the core of the Big Data ecosystem.

Inspired by Google publications about GoogleFS and MapReduce, Hadoop is a Java framework used by most Big Data technologies. This framework is composed of:

- Hadoop File System (HDFS): a distributed file system that allows you to store files on a cluster of servers like if it were just one disk

- Hadoop MapReduce: an implementation of MapReduce paradigm that allows you to write distrusted data processes by simple inheritance. The data processed are stored on HDFS.

Almost all Big Data technologies use HDFS, and a lot of also use MapReduce.

Sum-up of Big Data technologies

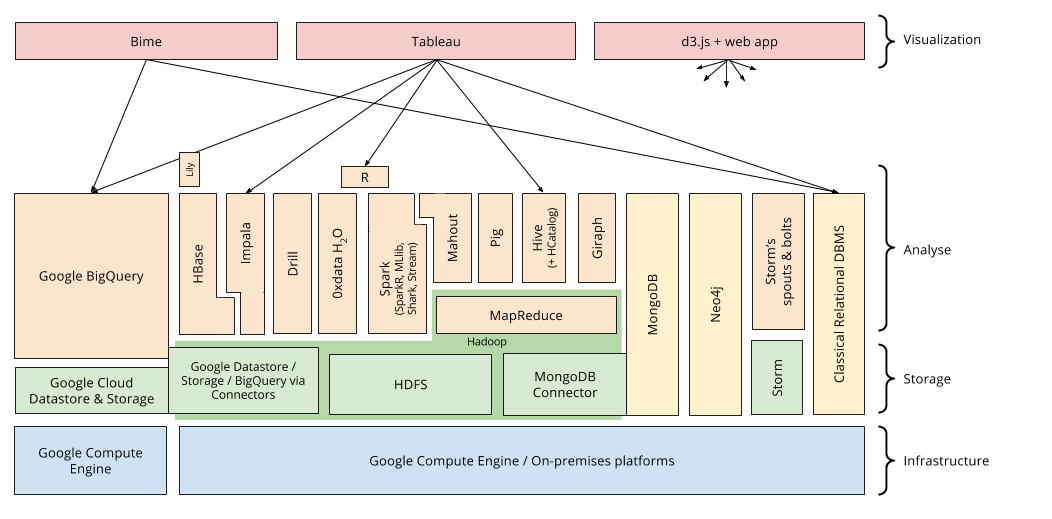

All those technologies constitute a huge Hadoop ecosystem that I will present quickly. This figure below present the most important Big Data solutions in the Hadoop ecosystem and the dependencies between them.

We can see four layers:

- The infrastructure that is to say machines that can either be on-premise (managed locally) or rented and hosted in the cloud.

- The storage that can either be HDFS or another distributed file system that implements the same interfaces.

- The interrogation / analysis through various solutions using MapReduce or not.

- The visualization of the results.

Without going into details, we can find solutions for:

- Data processing with classical programming (MapReduce, Spark, …) or through a dedicated language (Pig, …)

- NoSQL databases document oriented, graph oriented, column oriented, key-value oriented (MongoDB, Giraph, Neo4j, HBase, HCatalog, …)

- Data interrogation in pseudo-SQL, translating the request in a distributed data process (Hive, Impala BigQuery, Drill, Spark SQL, …)

- Machine Learning (Mahout, 0xdata H2O, Spark MLlib, …)

- Dataflow processing in real-time (Storm, Spark Streaming…)

This list of technologies is far from being exhaustive but it give a quite good overview of the various solutions.

Hadoop distributions

It is common to need more than one of these tools, and the dependencies and incompatibilities aren’t always easy to handle. That is why companies provide “Hadoop distributions” that is to say a prepackaged and preconfigured Hadoop ecosystem that allows you not to care about all this work of installation, configuration, dependencies and incompatibilities handling that can be quite unpleasant when you’re not an expert.

The main Hadoop distributions are made by Cloudera, HortonWorks and MapR.

Big Data evolution: the progression of Spark and the end of MapReduce

Each technology in the Big Data ecosystem has its usage, its pros and cons. Because of the boom of Big Data and the fact that it’s a field where we always look for better performance, the ecosystem evolves very quickly and new solutions appears regularly, aiming to improve the existing technologies.

I think that the best examples to illustrate this evolution are MapReduce and Spark.

MapReduce is a pattern described by Google in 2004, implemented quickly in Yahoo’s Nutch project that will become Apache Hadoop in 2008. In the history of Big Data, MapReduce is a dinosaur. It’s an algorithm that scales well on big volumes but it has some slowness, particularly visible on modest volumes.

Because of slowness of MapReuce, the solutions that wants to offer short processing time on modest volumes do not use MapReduce. Just for the anecdote, during Google I/O 2014, Google said that MapReduce paradigm already had 2 successors internally. The last one have been made available in SaaS under the name Google Cloud Dataflow.

We can therefore notice that all solutions that claim to be quick do not use MapReduce and use HDFS directly instead. The most significant example is Spark, a tool that allows you to write distrusted data processes very easily. It offers libraries for classical data processing, but also SQL interrogation, Machine Learning, graphs and real-time processing. It can either work on HDFS or with data in RAM for much better performance.

Even if Spark is still young, it has a huge community and is one of the most active Apache projects. This solution appears to be the successor of MapReduce and has advantage of centralizing most of the tools necessary in a Hadoop cluster.

Hadoop in the cloud

As we’ve seen, there are two ways for a Hadoop infrastructure: an on-premise infrastructure where you buy, host and maintain multiple servers (various activities that require skills and represent a cost); an infrastructure in the cloud with IaaS (Infrastructure as a Service) model where you rent servers that are hosted and managed for you. Let’s see this second case with more details.

For hosted Big Data, we can rent servers from classic hosters (for example 1&1) that rent servers for a month. However, this approach is technically identical to the on-premise approach except that you don’t have to manage the servers. According to me, this is not a real cloud approach.

The “true” cloud way comes from specialized hosting platform (particularly from Amazon and Google) that propose various services for scalable data processing, especially the rent of virtual machines for hours or even minutes if you want. Those offers include multiple services that pushes you into splitting the storage billed for the volume (Amazon S3, Google Cloud Storage) and the processing cluster billed for the processing time (Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2), Google Compute Engine). Therefore, whereas the storage is persistent, the processing cluster is ephemeral, allowing you to provision the necessary number of virtual machines for a process and delete those VMs once the process is finished.

This new approach is much more flexible and allows important saving if your cluster has a variable load. For example, MapR (Hadoop distribution provider) deployed 2103 VMs to sort 1.5 TB of data in 1 minutes for a cost of $20.

It is a quite disruptive approach because you need to prepare some automated deployment and configuration tools, but it offers an exceptional flexibility regarding the processing capacity of your cluster, impossible to reach with a standard approach.

It is important to notice that Amazon took this market a few years ago, launching Amazon EC2 in 2006 and Amazon Elastic MapReduce in 2009. Amazon currently trust Big Data cloud services. In comparison, Google launched Google Compute Engine in 2012. Amazon therefore have a big commercial advantage, whereas Google is just starting opening their incredibly powerful internal technologies to the public. However, it seems that’s the way Google is taking, because we can see various great Big Data tools opening to the public, such as BigQuery (very quick SQL interrogation of data) or Google Cloud Dataflow (internal successor to MapReduce).